Seventy years ago today Germany declared war on America.

Many people are mystified by Hitler’s decision to take on the most powerful economic power in the world – especially since the German army was mired in a conflict with the Soviet Union at the time, and Hitler had no real way of ever conquering America. What were the Germans going to do, invade Manhattan? They hadn’t even been able to cross the English Channel to land on the beaches of the south coast, so what chance did they have of ever crossing the vast Atlantic?

But Hitler’s thinking was not so crazy, and this decision is easy to explain. In essence, Hitler believed that the Germans were effectively already at war with America. The German declaration of war of 11 December 1941 accused Roosevelt of ‘virtually’ bringing America into the war three months before, as result of his decision to allow US ships in pursuit of their convoy protection duties to attack German warships in the Atlantic .

The head of the German navy, Grand Admiral Raeder, had told Hitler in the autumn of 1941 that it was all but impossible for the German navy to prevent American convoys reaching Britain. How could German submarines know which convoy protection ships were American – and avoid them – and which were British – and attack them?

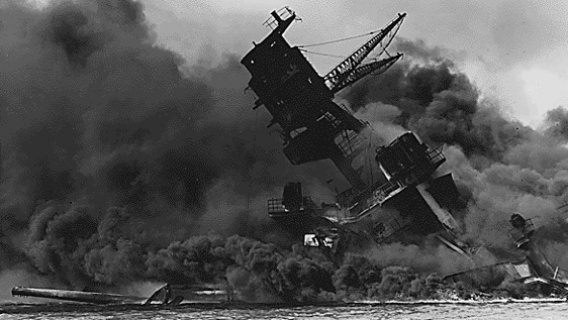

Moreover, Hitler was concerned that in the wake of the Pearl Harbour attack and the entry of America into the war against Germany’s ally, Japan, it was likely that Roosevelt would shortly declare war on Germany himself. Hitler, for reasons of prestige and no doubt still smarting from the British and French decision to declare war on Germany on 3 September 1939, thought that great nations declared war on other nations, they didn’t wait for others to decide to fight them.

It didn’t even matter to Hitler that Todt, his armaments minister, told him that with the resources of America behind them, the British were all but unbeatable. Hitler still believed that Germany’s future would be decided on the Eastern front. If the Soviet Union could be defeated then American involvement in the war would be an irrelevance.

Those were the thoughts that were in Adolf Hitler’s mind 70 years ago today.

Twitter

Twitter